Executive Summary

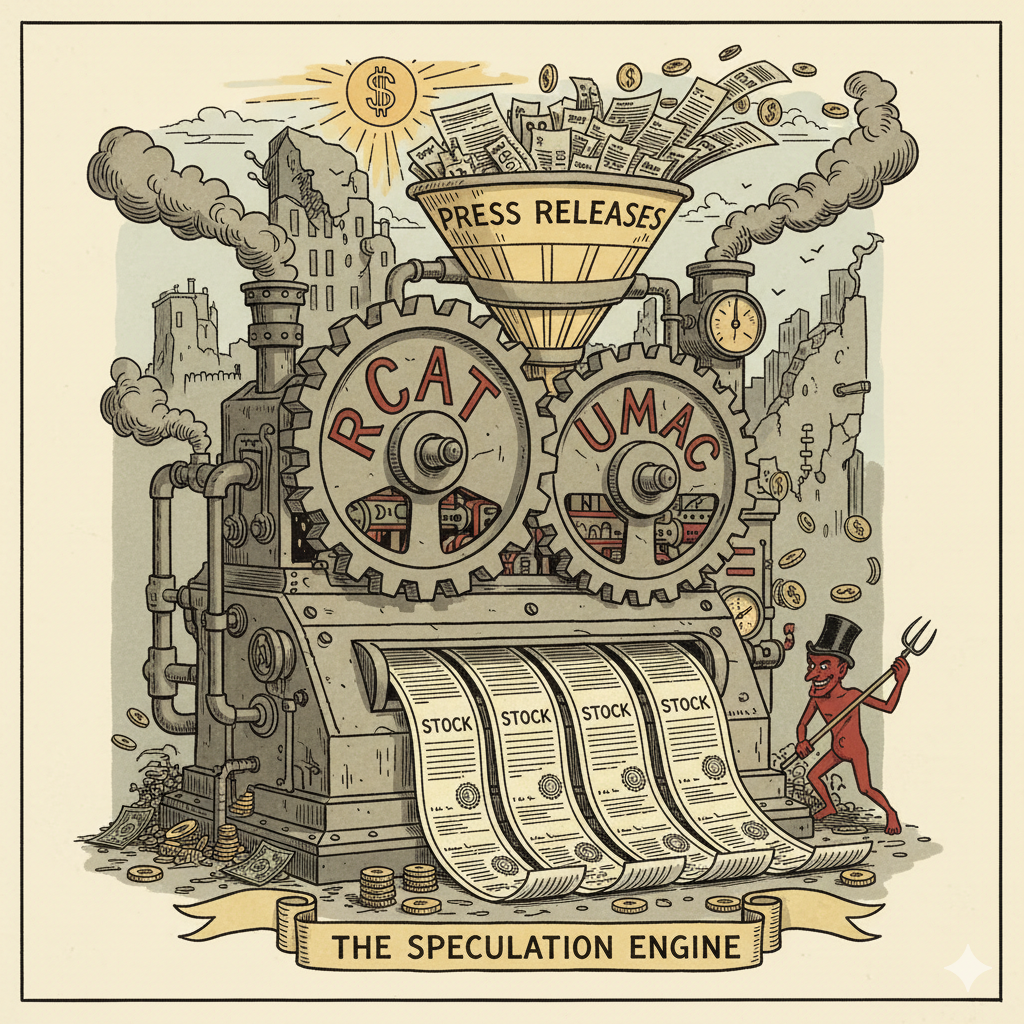

An in-depth investigation reveals a sophisticated and potentially fraudulent ‘Dilution-Hype Cycle.’ This cycle is at the core of Red Cat Holdings, Inc. (NASDAQ: RCAT) and Unusual Machines, Inc. (NYSE American: UMAC). The scheme appears strategically designed to perpetually extract capital from public markets.

This report details the interconnected corporate structure between the two companies. It analyzes the financial mechanics of their capital-raising activities and deconstructs their product and contract claims.

Our findings indicate the relationship between RCAT and UMAC is not a standard, arm’s-length corporate separation. It originated from RCAT’s divestiture of its consumer division. This move appears to be a strategic maneuver. It created a publicly-traded, controlled entity to facilitate a cycle of capital raising and stock promotion.

Key elements of this structure include:

- A Controlled Spin-Off: RCAT spun off its Rotor Riot and Fat Shark brands into UMAC. The transaction was paid for predominantly with UMAC stock, establishing RCAT as UMAC’s largest shareholder.

- Interlocking Management: A key RCAT executive was transferred to the CEO position at UMAC. This move ensures continued alignment and control.

- Non-Arm’s-Length Transactions: The interconnected relationship enables self-serving deals. A widely publicized $800,000 component order from RCAT to UMAC, for example, served to generate a positive news cycle and inflate the stock prices of both entities.

Both companies are characterized by significant and persistent unprofitability. This makes them dependent on the capital markets for survival. They service this dependency through a continuous pattern of dilutive stock offerings, frequently managed by a common underwriter, ThinkEquity. This process appears to be the core business model.

Furthermore, third-party analysis has challenged the veracity of the companies’ product claims and contract values. Allegations suggest key products are rebranded consumer drones with Chinese-made components. The analysis also claims the value of a pivotal government contract has been significantly overstated, creating a potential revenue shortfall of approximately $57 million.¹

These activities, viewed in aggregate, bear the hallmarks of a coordinated stock promotion and financing scheme. The scheme utilizes related-party transactions and a circular corporate structure. The primary objective appears to be generating hype to facilitate the continuous sale of equity, a practice that may not serve the best interests of independent shareholders.

(more…)