Executive Summary & Key Findings

A critical analysis of the 100-megawatt (MW) solar Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) between Microsoft and Shizen Energy reveals a partnership driven by converging needs in Japan’s complex energy market.

For Microsoft, the deal provides a crucial foothold to power its USD 2.9 billion expansion of data center and AI infrastructure.¹ This allows the company to meet its corporate sustainability mandates.² For Shizen Energy, the 20-year agreement with a premier corporate partner delivers the long-term revenue certainty needed to secure financing and validate its business model.³

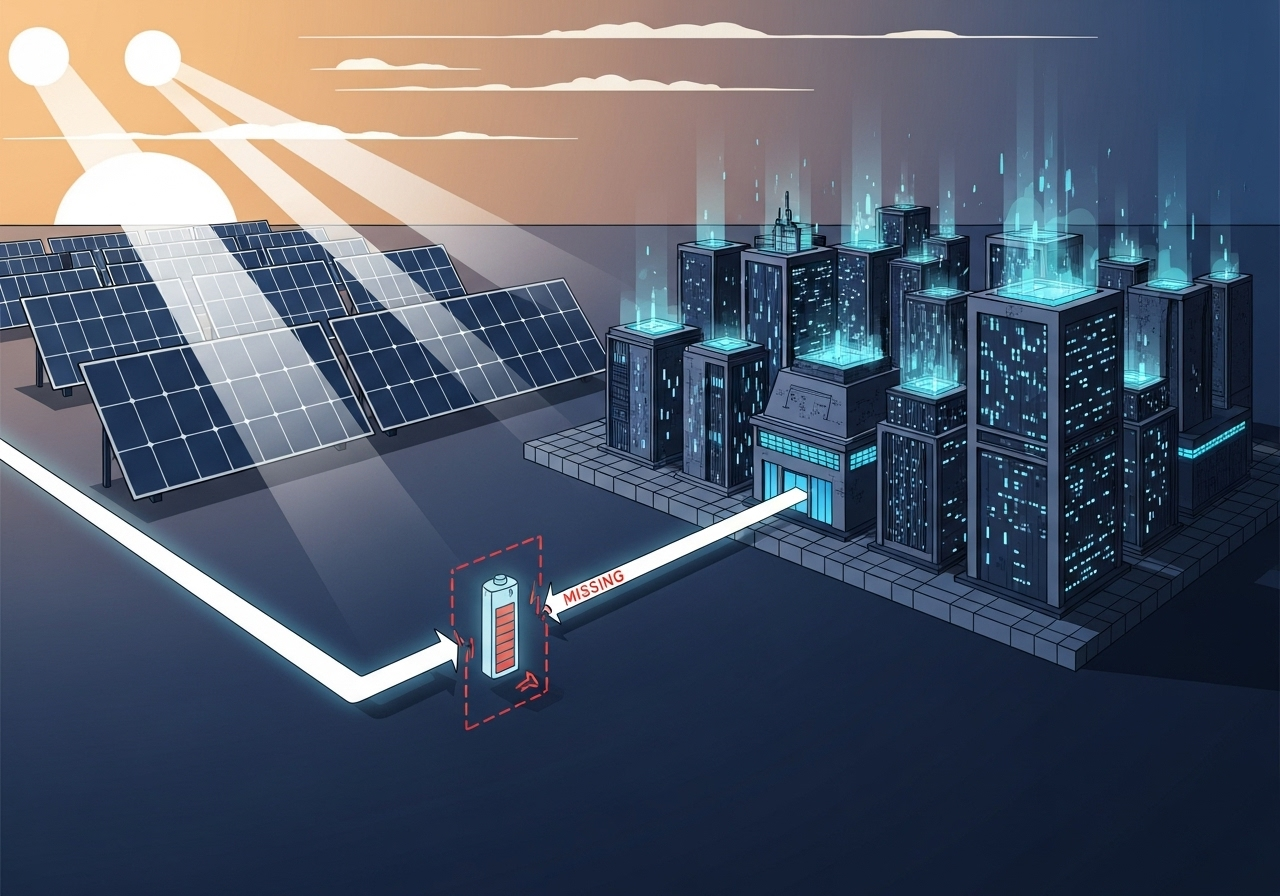

A central paradox of the agreement is the placement of the new solar projects in the Kyushu and Chugoku regions. These areas boast Japan’s highest solar irradiance but also suffer from the nation’s most severe grid congestion and renewable energy curtailment.⁴

The decision to proceed without co-located battery storage presents a significant, unaddressed risk. Grid-mandated shutdowns during periods of oversupply will lead to direct financial losses and unrealized clean energy generation.⁴ This suggests a calculated trade-off, prioritizing lower upfront capital costs to secure the landmark deal over long-term operational efficiency.

Shizen Energy’s financial capacity to undertake these projects is substantially fortified by a JPY 70 billion (approx. USD 474 million) investment framework with the Canadian pension fund CDPQ.⁵ This capital provides the stability required to navigate market risks. These risks include grid constraints and an evolving policy landscape, such as the shift from a fixed Feed-in Tariff (FIT) to a market-based Feed-in Premium (FIP) system.⁶

This PPA is an important step toward Microsoft’s 2025 goal of matching 100% of its annual electricity use with renewable purchases.² However, it is a more modest step toward its ambitious 2030 “100/100/0” goal of matching consumption with zero-carbon energy on an hourly basis.⁷

Ultimately, the Microsoft-Shizen agreement serves as a powerful market signal. It demonstrates a clear willingness from a major international corporation to engage deeply with Japan’s complex regulatory and grid environment. This commitment exerts tangible pressure on Japanese policymakers and grid operators. They must now accelerate market reforms and invest in the critical infrastructure needed to meet both corporate and national climate targets.²

Deconstruction of the Agreement: The Foundational Pillars

This section deconstructs the agreement’s core components to establish a factual baseline. It details the parties involved, the asset portfolio, and the contractual and operational frameworks.

The Parties: Profiles and Motivations

The agreement represents a convergence of interests between a global technology giant with immense energy needs and a leading domestic developer with local expertise.

Offtaker: Microsoft Corporation. As a global leader in cloud computing and AI, Microsoft’s energy consumption is expanding rapidly. The company announced a USD 2.9 billion investment to significantly expand its cloud and AI infrastructure in Japan.¹ This expansion creates a massive new electricity demand. The PPA is a direct response, providing a clear pathway to power its Japanese data centers with locally sourced, additional renewable energy.²

Developer: Shizen Energy Inc. Founded in June 2011 after the Great East Japan Earthquake, Shizen Energy aims to accelerate the transition to renewable energy.⁸ Based in Fukuoka, it has become one of Japan’s leading independent renewable energy developers.

Shizen’s key strength is its end-to-end control over the project lifecycle. It has in-house subsidiaries for Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) and long-term Operations and Maintenance (O&M).⁹ This structure allows for streamlined project delivery. The company has a global portfolio exceeding 1 GW and aims to develop 8 GW of capacity by 2030, making partnerships with large offtakers like Microsoft essential to its growth.¹⁰

The Asset Portfolio: A 100 MW Solar Aggregation

The 100 MW capacity is aggregated across a portfolio of four distinct solar power plants, a common development strategy in Japan.

- Total Capacity: The agreement covers 100 MW of solar power capacity through four separate project contracts.¹¹

- Project Breakdown:

- Project 1 (Announced 2023): The foundational project is the 25 MWac Inuyama Solar Power Plant in Aichi Prefecture. This was Microsoft’s first renewable energy PPA in Japan and began operations in February 2024.¹

- Projects 2, 3, & 4 (Announced 2025): Three additional agreements achieve the 100 MW total. These projects have a combined capacity of approximately 75 MW and are located in the Kyushu and Chugoku regions.²

- Project Status: The portfolio’s development is staggered. One new project in Kyushu is already operational, while the other two are under construction.² All four projects have successfully reached financial close, indicating strong investor confidence.¹¹

- Probable Locations: While not officially confirmed, public data from Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) strongly indicates the inclusion of two specific projects. A 25.9 MWac project in Shimane Prefecture and a 20 MWac project in Oita Prefecture were awarded Feed-in-Premium contracts and align with the PPA’s capacity and regional descriptions.¹

The Contractual Framework: A 20-Year Commitment

The long-term nature of the agreements provides the financial certainty required for new-build renewable energy projects.

- Structure: The agreements use a 20-year Power Purchase Agreement structure.² The initial 25 MW deal is a Virtual PPA (VPPA), and the subsequent agreements likely follow a similar financial model.¹² VPPAs do not require physical electricity delivery, offering flexibility for buyers like Microsoft.¹³

- Timeline: The partnership began with the first 25 MW agreement in October 2023. The expansion to the full 100 MW was announced on October 3, 2025, signaling a rapidly strengthening relationship.¹¹

The Operational Framework: An Integrated Approach

Shizen Energy’s corporate structure is a key enabler of the agreement, providing a single point of accountability for the entire project lifecycle.

- EPC and O&M: Shizen Energy utilizes its in-house subsidiaries to execute the projects. Shizen Engineering Inc. is responsible for the EPC of at least one new project. Upon completion, Shizen Operations Inc. will manage all four plants.¹¹

- De-Risking through Integration: This integrated model is a crucial de-risking mechanism. By keeping EPC and O&M functions in-house, Shizen Energy maintains direct control over quality, timelines, and operational performance. This provides a high degree of assurance to a risk-averse partner like Microsoft that the projects will be built to specification and maintained for optimal output over the two-decade contract term.

Geographical & Technical Viability Assessment

This section applies a critical lens to the physical aspects of the agreement. It assesses the projects’ locations, the technical challenges of the regional grid, and the expected lifecycle performance of the solar technology.

Site Analysis: The Double-Edged Sword of Kyushu and Chugoku

The choice of western Japan for the new solar projects is a strategic trade-off. It balances Japan’s best solar resources against its most constrained grid infrastructure.

- High Solar Potential: The Kyushu and Chugoku regions benefit from some of the highest levels of solar irradiance in Japan, making them a logical choice for developing solar assets.¹⁴ At certain peak times, solar power has covered as much as 76% of the entire electricity demand in the Kyushu region.¹⁵

- Climate Viability: Japan’s climate is broadly conducive to solar energy. However, western Japan’s specific conditions introduce variables that must be managed. These include high summer humidity, the risk of typhoons, and significant seasonal variation in output. Shizen Operations Inc.’s operational planning and risk management must account for these factors.

The Curtailment Challenge: A Critical Unpriced Risk

The most significant challenge facing these projects is the grid’s capacity to absorb the power they produce.

- Grid Congestion: The Kyushu region is often described as an “electricity island.” It is connected to Japan’s main island only via a limited-capacity interconnection, which severely restricts its ability to export surplus electricity.⁴

- Record Curtailment: A massive build-out of solar capacity, low demand during mild seasons, and the inflexible operation of regional nuclear power plants have led to a chronic oversupply of electricity. This forces the grid operator to “curtail,” or deliberately shut down, renewable generators to maintain stability. Kyushu suffers from the highest rates of curtailment in Japan, with the projected rate reaching a record of nearly 7% in fiscal year 2023.⁴

- Economic Impact: Curtailment represents a direct financial loss. When a solar plant is curtailed, it cannot export electricity, and its owner is not compensated. In a VPPA, this lost output directly and negatively impacts the financial settlement between Microsoft and Shizen Energy.

Asset Lifecycle & Performance: The Long-Term View

The 20-year PPA term necessitates a detailed examination of the long-term performance and maintenance costs of the solar panels.

- Solar Panel Degradation and Longevity:

- The industry standard for a solar panel’s “useful life” is 25 to 30 years, aligning well with the 20-year PPA term.¹⁶

- Solar panels experience a natural decline in power output over time, known as degradation. The typical degradation rate is between 0.5% and 0.8% per year.¹⁷ After 20 years, the panels can be expected to produce approximately 90% of their original nameplate capacity.¹⁶

- Operational Expenditure Analysis: Dust and Cleaning:

- The accumulation of dust, dirt, and other debris on the panel surface blocks sunlight and reduces electricity generation.¹⁷

- Regular cleaning is a required component of the O&M plan to mitigate these losses. Professional cleaning is typically recommended every six months, with estimated annual costs in the range of USD 500 to USD 700 per site.¹⁸ Shizen Operations Inc. bears these recurring costs, which are factored into the PPA price.

The decision to proceed in a heavily curtailed region without battery storage is a calculated risk. While it lowers initial capital investment, the ongoing financial losses from curtailment create a powerful incentive for future action. This provides a strong business case for a potential “Phase 2” of the project involving retrofitting the sites with battery storage.

Furthermore, the direct financial impact on a major corporation like Microsoft provides a compelling argument for policy advocacy. Microsoft has a history of working with governments to remove grid bottlenecks and may use performance data from these projects to lobby for necessary grid upgrades and market reforms in Japan.¹⁹

The following table projects the portfolio’s energy output over a 25-year lifecycle, accounting for natural panel degradation.

Table 1: Solar Panel Lifecycle Projections for 100 MW Portfolio

| Year of Operation | Assumed Annual Degradation Rate | Annual Output as % of Year 1 | Estimated Annual Output (GWh) | Cumulative Output Loss (GWh) |

| 1 | – | 100.0% | 120.00 | 0.00 |

| 5 | 0.5% | 98.0% | 117.62 | 5.94 |

| 10 | 0.5% | 95.6% | 114.70 | 25.86 |

| 15 | 0.5% | 93.2% | 111.88 | 59.10 |

| 20 | 0.5% | 90.9% | 109.04 | 105.02 |

| 25 | 0.5% | 88.6% | 106.30 | 163.02 |

| Note: Projections are based on a 14% capacity factor for the 100 MW portfolio, yielding an estimated 120 GWh in Year 1 (Source: International Energy Agency averages for Japan).²⁰ A median annual degradation rate of 0.5% is applied.¹⁷ |

Financial and Corporate Analysis

This section scrutinizes the financial underpinnings of the PPA. It examines Shizen Energy’s stability, the role of its key investors, and the government incentives that make the deal commercially viable.

Shizen Energy: Financial Health and Strategic Position

Shizen Energy’s ability to secure a landmark deal with Microsoft results from its strong financial footing and strategic partnerships.

- Financial Performance: While Shizen Energy is a private company, reports from investor and partner SIGMAXYZ Investment Inc. provide a strong proxy for its financial ecosystem. For fiscal year 2023, the associated entity reported consolidated revenue of JPY 22.41 billion (a 29% year-over-year increase) and an ordinary profit of JPY 4.33 billion (a 33% increase). The balance sheet shows a healthy equity ratio and no borrowings.²¹ This positive trend continued into the first quarter of fiscal year 2024.²²

- The CDPQ Investment as a Cornerstone: A transformative event for Shizen Energy occurred in October 2022. The company secured a massive financing package from Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ), including a JPY 20 billion direct investment and a JPY 50 billion co-investment framework.⁵ This capital provides the long-term funding necessary to develop a large pipeline of renewable energy projects.⁵ The 25 MW Inuyama solar plant, the first project in the Microsoft PPA, was also the first co-investment made under this CDPQ framework.²³

- Strategic Role of the Microsoft Deal: The 100 MW PPA with Microsoft is a cornerstone asset for Shizen Energy. It provides a guaranteed, 20-year revenue stream from an AAA-rated corporate counterparty, which is the gold standard for project finance. As a Shizen executive noted, securing such a long-term agreement was pivotal in obtaining project financing from domestic and international financial institutions.¹¹ The deal also cements Shizen’s status as a preferred developer for multinational technology companies, a reputation further solidified by a similar PPA with Google.²⁴

Incentive Structures and Market Mechanisms

The agreement is enabled by a deliberate shift in Japanese government policy designed to move renewable energy projects towards market-based mechanisms.

- Shift from FIT to FIP: Japan has been transitioning from a Feed-in Tariff (FIT) system, which offered a high, fixed price for renewable energy, to a Feed-in Premium (FIP) system, effective April 2022.⁶ Under the FIP scheme, a project sells its electricity into the wholesale market and receives an additional government-set “premium” on top. This structure exposes the project to market dynamics while still providing revenue support, creating an environment where contracts like PPAs can thrive.⁶

- FIP Application in the Microsoft PPA: The FIP scheme is directly relevant to this deal. Public data from METI’s 18th Solar Auction reveals that projects matching the description of those in the PPA portfolio were awarded FIP contracts at a rate of JPY 7.94 per kWh.¹

- Tax Breaks and Direct Incentives: While the FIP scheme serves as the primary financial incentive, the available research does not specify any particular tax breaks applied to these projects.⁶ The absence of detailed information on such incentives in public disclosures is a notable information gap, but it underscores the central role of the FIP in the project’s financial structure.

The following table provides a financial snapshot of SIGMAXYZ Investment Inc., a key investor and partner, which serves as a proxy for the financial health of Shizen Energy’s ecosystem.

Table 2: SIGMAXYZ Investment Inc. – Financial Snapshot (FY22-FY23)

| Financial Metric | FY2022 (JPY mn) | FY2023 (JPY mn) | Year-over-Year Change (%) |

| Revenue | 17,334 | 22,410 | +29% |

| Operating Profit | 3,235 | 4,232 | +31% |

| Ordinary Profit | 3,265 | 4,338 | +33% |

| Total Assets | 14,461 | 18,295 | +27% |

| Net Assets | 10,878 | 13,193 | +21% |

| Equity Ratio (%) | 75% | 72% | -3 pts |

| Source: Consolidated financial statements for SIGMAXYZ Investment Inc., an investor and partner of Shizen Energy.²¹ |

Technology and Supply Chain Scrutiny

This section examines the physical hardware and systems involved. It focuses on the strategic decision to omit battery storage and scrutinizes the geopolitical risks embedded in the solar panel supply chain.

The Battery Question: A Notable Absence

Public disclosures consistently omit any mention of co-located Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS). This absence creates a strategic contradiction.

- Contradiction with Market Needs: The new projects are in the regions most severely affected by renewable energy curtailment in Japan.⁴ Battery storage is the primary technological solution, allowing excess solar generation to be stored and discharged during evening hours.

- Contradiction with Developer Capabilities: The decision is puzzling given that Shizen Energy possesses advanced, in-house capabilities in energy storage and grid management through its subsidiary, Shizen Connect.²⁵

- Implication of the Omission: The most plausible explanation is a deliberate decision to minimize initial project capital expenditure (CAPEX). Securing Microsoft’s first major PPA in Japan was a landmark achievement, and adding the significant cost of large-scale batteries could have made the project’s economics less attractive. However, this decision leaves significant economic value unrealized and exposes the project to the full financial impact of grid curtailment.

Solar Panel Sourcing and Geopolitical Risk

The physical solar panels are products of a global supply chain fraught with concentration risk and geopolitical tension.

- Japan’s Import Dependency: Despite having over 91 GW of installed solar capacity, Japan is now heavily reliant on imports for panels and their components.²⁶ These imports were valued at an estimated USD 9.6 billion in 2024-25.²⁷

- Dominance of China and Southeast Asia: The global solar PV supply chain is overwhelmingly concentrated in China, which controls over 80% of manufacturing capacity.²⁸ A significant share of panels imported by Japan originate from factories in Southeast Asian nations like Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand. These facilities are often owned by Chinese parent companies and dependent on Chinese components.²⁹

- Geopolitical Vulnerabilities: This extreme concentration creates significant and unavoidable geopolitical risks.³⁰

- Trade Tensions: The supply chain is highly vulnerable to disruption from trade disputes, tariffs, and sanctions, which can lead to global price volatility and supply shortages.²⁸

- Supply Chain Chokepoints: China’s near-monopoly on critical upstream materials, such as polysilicon, creates a strategic chokepoint that could be exploited for political leverage or disrupted by domestic policy changes.²⁸

- “De-risking” Imperative: In response, a global trend towards “de-risking” and diversifying critical supply chains is underway.³¹ Developers like Shizen Energy likely mitigate these risks through strategies such as multi-sourcing from different suppliers and maintaining contractual clauses that account for supply chain disruptions, though the project remains inherently exposed to these macro-level vulnerabilities.

Market Context and Strategic Implications

This section places the agreement within the dual contexts of Japan’s evolving corporate PPA market and Microsoft’s ambitious global sustainability strategy to fully grasp its significance.

Benchmarking the Deal: Scale and Significance

While a 100 MW PPA is a substantial undertaking, its true importance is best understood relative to the broader market landscape.

- A Nascent but Growing Market: The corporate PPA market in Japan is young but expanding rapidly. The first deal was signed in 2021, but by September 2025, the market had grown to over 500 disclosed agreements representing over 2.5 GW in capacity.³² The number of publicly announced deals grew by 18% in 2024 alone.³³

- Comparative Scale: In this context, the 100 MW Microsoft-Shizen portfolio is a significant addition. It is among the largest corporate PPAs announced to date, though other major deals include a 120 MW solar park for Nippon Steel³⁴ and Google’s 60 MW of PPAs (partially with Shizen Energy).²⁴

- Strategic Importance Over Absolute Size: The deal’s primary significance lies not in its absolute megawatt capacity but in its strategic nature. It represents a long-term commitment by one of the world’s most influential technology companies in a key global market. This action sets a powerful precedent and a competitive benchmark for other multinational corporations operating in Japan.

Microsoft’s Evolving Carbon Strategy: From 100% Renewable to 100/100/0

The PPA with Shizen must be analyzed through the lens of Microsoft’s two-tiered and evolving decarbonization goals.

- The 2025 Goal: 100% Annual Matching: Microsoft’s near-term target is to match 100% of its annual electricity consumption with renewable energy purchases.² This is an accounting-based goal, and the 100 MW PPA with Shizen, generating approximately 120 GWh annually, directly contributes to meeting it.²⁰

- The 2030 Goal: 100/100/0 Hourly Matching: Microsoft’s more ambitious goal for 2030 is “100/100/0.” This means matching 100% of its electricity consumption, 100% of the time, with purchases from zero-carbon energy sources on the same regional grids where the consumption occurs.⁷

- The Strategic Gap: This is where the limitations of a solar-only PPA become clear. Solar power is intermittent. While this portfolio will help Microsoft match its daytime energy load at its Japanese data centers, it provides no solution for nighttime energy consumption. To achieve a true 100/100/0, Microsoft must procure a diverse portfolio of firm and complementary carbon-free energy sources, including wind, geothermal, and, most critically, energy storage.

- A Skeptical Viewpoint: From the perspective of the 100/100/0 vision, this 100 MW solar PPA is a necessary but profoundly insufficient first step. It solves a piece of the 24-hour energy puzzle while highlighting the much larger challenges that must be overcome to achieve true, granular, 24/7 carbon-free energy.

This table benchmarks the 100 MW Microsoft-Shizen deal against other significant corporate PPAs announced in Japan between 2023 and 2025.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Major Corporate PPAs in Japan (2023-2025)

| Offtaker | Developer/Supplier | Capacity (MW) | Technology | PPA Type | Announcement Year |

| Microsoft | Shizen Energy | 100 | Solar | Virtual | 2023-2025 |

| Nippon Steel | Self-developed | 120 | Solar | On-site/Private Line | 2024 |

| Shizen Energy & CEC | 60 | Solar | Virtual | 2024 | |

| PAG Renewables | Self-developed | 28.8 | Solar | Off-site Physical | 2023 |

| Kao Corporation | Mizuho Leasing Group | 15.6 | Solar | Virtual | 2023 |

| OSAKA Titanium | Sojitz / KEPCO | 10 | Solar (Distributed) | Off-site Physical | 2025 |

| Sources: Microsoft/Shizen Energy,² Nippon Steel,³⁴ Google,²⁴ PAG Renewables,³⁵ Kao Corporation,³⁶ OSAKA Titanium.³⁷ PPA Type for some projects is inferred based on descriptions. |

Synthesis and Forward-Looking Analysis

This final section synthesizes the preceding analysis. It presents a holistic view of the agreement’s risks and opportunities and offers a forward-looking perspective on its likely evolution.

Risk and Opportunity Matrix

A balanced assessment of the agreement highlights several key factors that will determine its long-term success.

- Key Risks

- Grid & Curtailment (High): The single greatest near-term risk is the severe grid congestion in Kyushu and Chugoku. Without integrated battery storage, the projects are fully exposed to curtailment, which translates directly to lost revenue.

- Supply Chain Geopolitics (Medium): The project is exposed to the risks inherent in a global solar supply chain heavily concentrated in China. Potential trade disputes or logistical disruptions could impact the cost and availability of replacement parts.

- Regulatory Volatility (Low-Medium): Japan’s energy policies are in a state of managed evolution. Future changes to the FIP scheme, grid access rules, or market pricing mechanisms could alter the project’s underlying economics over its 20-year lifespan.

- Key Opportunities

- First-Mover Advantage (High): By executing one of the first large-scale corporate PPAs in Japan, Microsoft establishes itself as a serious and committed player, which can provide an advantage in securing access to the best future projects.

- Long-Term Price Hedge (High): The 20-year fixed-price nature of the PPA provides Microsoft with a valuable hedge against the long-term volatility of the wholesale electricity market in Japan.

- Platform for Growth (High): The established partnership with a capable developer like Shizen Energy creates an ideal platform for future collaboration on more complex projects involving battery storage, offshore wind, and advanced grid services.

Future Outlook and Skeptical Recommendations

Based on the analysis, several future developments can be anticipated.

- The Inevitability of Storage: The economic logic for integrating battery storage at these solar sites is compelling. The financial losses from ongoing curtailment will create a powerful, data-driven business case for retrofitting the facilities with BESS. A follow-on announcement regarding a storage component to this portfolio should be anticipated within the next two to three years.

- From PPA to Policy Influence: Microsoft is not a passive energy buyer. It is highly probable that the company will use operational data from this portfolio—specifically on lost generation due to curtailment—to engage in direct policy advocacy with METI and regional utilities. This advocacy could pressure authorities to accelerate grid modernization, introduce market reforms like negative pricing, and create stronger policy support for energy storage. These changes would fundamentally improve the investment climate for all renewable energy producers in Japan.⁴

- The Real Test Ahead: This 100 MW solar agreement, while a significant achievement, should be viewed as the opening move in a much longer strategy. The true test of Microsoft’s decarbonization ambitions in Japan will lie in the next wave of projects. Success will be defined not by procuring intermittent renewables alone, but by the ability to finance and deploy the technologies required for a 24/7 carbon-free grid: large-scale offshore wind, firm power sources, and the widespread integration of battery storage.

In conclusion, this skeptical inquiry reveals the Microsoft-Shizen PPA to be a strategically pragmatic but incomplete step. It is a foundational move whose ultimate success hinges on future investments in storage and substantive reforms to Japan’s energy market.

Works Cited

- Japan Energy Hub. “Shizen Energy’s contracted PPA capacity with Microsoft reaches 100MW across four solar projects.” October 6, 2025. https://japanenergyhub.com/news/shizen-energys-contracted-ppa-capacity-with-microsoft-reaches-100mw-across-four-solar-projects/

- ESG News. “Microsoft Expands Clean Energy Portfolio in Japan with New Shizen Solar Deals.” October 3, 2025. https://esgnews.com/microsoft-expands-clean-energy-portfolio-in-japan-with-new-shizen-solar-deals/

- Blackridge Research. “Shizen Energy Achieves 100 MW in Renewable Energy Purchase Agreements with Microsoft for Solar Projects in Japan.” October 3, 2025. https://www.blackridgeresearch.com/news-releases/shizen-energy-achieves-100-mw-renewable-energy-purchase-agreements-microsoft-for-solar-projects-japan

- Renewable Energy Institute. “Curtailment of Solar and Wind Power in Japan Reaches New Record High in Fiscal Year 2023.” April 11, 2024.(https://www.renewable-ei.org/en/activities/column/REupdate/20240411.php)

- La Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ). “Shizen Energy and CDPQ announce JPY 70-billion (USD 474-million) investment by CDPQ to accelerate the energy transition in Japan and key international markets.” October 24, 2022. https://www.lacaisse.com/en/news/pressreleases/shizen-energy-cdpq-announce-jpy-70-billion-usd-474-million-investment-cdpq

- Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP. “Japan Renewables Alert Series (Vol. 2) – Feed-in Premium to Start in April 2022.” March 2022.(https://www.orrick.com/en/Insights/2022/03/Japan-Renewables-Alert-58)

- Microsoft. “Made to measure: Sustainability commitment progress and updates.” July 14, 2021. https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2021/07/14/made-to-measure-sustainability-commitment-progress-and-updates/

- Shizen Energy Inc. “Our Story.” Accessed October 2025. https://www.shizenenergy.net/en/

- Shizen Energy Inc. “Company Overview.” Accessed October 2025. https://www.shizenenergy.net/en/about/company/

- JIC Venture Growth Investments. “Shizen Energy Inc.” October 2022. https://www.j-vgi.co.jp/en/portfolio/shizenenergy

- Shizen Energy Inc. “Shizen Energy Reaches 100 MW Mark in Long-Term Renewable Energy Purchase Agreements with Microsoft for Japan Solar Projects.” October 3, 2025. https://www.shizenenergy.net/en/2025/10/03/seg_vppa_microsoft_100mw/

- Carbon Credits. “Microsoft Expands Japan’s Green Grid with Shizen Energy’s 100 MW Solar Push.” October 2025. https://carboncredits.com/microsoft-expands-japans-green-grid-with-shizen-energys-100-mw-solar-push/

- Renewable Energy Institute. “Corporate PPA: Latest Trends in Japan (2025 Edition).” March 2025.(https://www.renewable-ei.org/pdfdownload/activities/REI_ENCorporatePPA_2025.pdf)

- MDPI. “A Novel Forecasting Method to Reduce Variable Renewable Energy Curtailment in Kyushu, Japan.” Energies. September 2020. https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/13/18/4703

- Renewable Energy Institute. “Solar covered 76% of a demand in Kyushu at its peak generation.” July 4, 2017. https://www.renewable-ei.org/en/activities/column/20170704.html

- Waaree Energies Ltd. “How Long Do Solar Panels Last & What Is Solar Panels Degradation?” Accessed October 2025. https://waaree.com/blog/solar-panels-degradation/

- MySolarfy. “Solar Panel Degradation Rates: What You Need to Know.” Accessed October 2025. https://mysolarfy.com/solar-panel-degradation-rates/

- EcoFlow. “How Much Does Solar Panel Cleaning Cost?” Accessed October 2025. https://www.ecoflow.com/us/blog/how-much-does-solar-panel-cleaning-cost

- Microsoft. “Powering progress in Asia: AI and energy.” September 2, 2025. https://news.microsoft.com/source/asia/2025/09/02/powering-progress-in-asia-ai-and-energy/

- FindArticles. “Microsoft Goes Solar in Japan with 100 MW Deal.” October 6, 2025. https://www.findarticles.com/microsoft-goes-solar-in-japan-with-100-mw-deal/

- SIGMAXYZ Investment Inc. “FY23 Consolidated Financial Results.” May 21, 2024. https://data.swcms.net/file/sigmaxyz-clump/dam/jcr:fc47c5dd-3cf3-4e56-8466-40092572fe9c/140120240521502520.pdf

- SIGMAXYZ Investment Inc. “Q1 FY24 Consolidated Financial Results.” August 8, 2024. https://data.swcms.net/file/sigmaxyz-clump/dam/jcr:d6e89902-7864-4fdf-9b1e-4e30a90225dc/140120240808567236.pdf

- La Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ). “CDPQ acquires 80% stake in a solar plant in Japan.” February 14, 2024. https://www.lacaisse.com/en/news/pressreleases/cdpq-acquires-80-stake-solar-plant-japan

- PV Tech. “Google signs first solar PPAs in Japan for 60MW of capacity.” October 2025. https://www.pv-tech.org/google-signs-first-solar-ppas-japan-60mw-capacity/

- Shizen Energy Inc. “Shizen Connect provides EMS for on-site PPA with battery storage at Nishi-Nippon Railroad’s large-scale distribution base.” November 15, 2024. https://www.shizenenergy.net/en/2024/11/15/shizen-connect-provides-ems-for-on-site-ppa-with-battery-storage-at-nishi-nippon-railroads-large-scale-distribution-base/

- Wikipedia. “Solar power by country.” Accessed October 2025.(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_power_by_country)

- TradeImex. “Global Solar Panel Import Data 2024-25: Top Importers by Country.” 2025. https://www.tradeimex.in/blogs/global-solar-panel-import-data-2024-25-top-importers-by-country

- International Energy Agency. “Solar PV Global Supply Chains.” 2022. https://www.iea.org/reports/solar-pv-global-supply-chains/executive-summary

- Volza. “Solar Panel Import Data of Japan.” October 2024. https://www.volza.com/p/solar-panel/import/import-in-japan/

- ResearchGate. “Geopolitical Risks of Climate Change Mitigation.” July 1, 2022.(https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361864913_Geopolitical_Risks_of_Climate_Change_Mitigation)

- Lazard. “The Geopolitics of Supply Chains.” 2024. https://www.lazard.com/media/d4dnwbvc/the-geopolitics-of-supply-chains.pdf

- Japan Energy Hub. “CPPAs in 2025: Market Overview, Trends and Opportunities (Report).” September 2025. https://japanenergyhub.com/corporate-ppas-report-2025/

- JAPAN NRG. “Japan’s PPA Contract Volume and Size Expanded in 2024 Amid Push for More Variety.” March 17, 2025. https://japan-nrg.com/deepdive/japans-ppa-contract-volume-and-size-expanded-in-2024-amid-push-for-more-variety/

- GlobeNewswire. “Japan Solar Power Generation Market to Hit Valuation of US$ 12.21 Billion By 2033: Astute Analytica.” July 11, 2025.(https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/07/11/3114103/0/en/Japan-Solar-Power-Generation-Market-to-Hit-Valuation-of-US-12-21-Billion-By-2033-Astute-Analytica.html)

- PAG. “PAG Renewables Announces Landmark 30-Year Corporate PPA.” October 3, 2023. https://www.pag.com/en/pag-renewables-announces-landmark-30-year-ppa

- Kao Corporation. “Kao Concludes One of the Largest VPPAs in Japan.” June 9, 2023. https://www.kao.com/global/en/newsroom/news/release/2023/20230609-001/

- pv magazine. “Sojitz, Kansai Electric sign 20-year PPA to power titanium plant in Japan.” June 9, 2025. https://www.pv-magazine.com/2025/06/09/sojitz-kansai-electric-sign-20-year-ppa-to-power-titanium-plant-in-japan/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.